How we caught the Miramar stoat

This story was taken from our 2023/24 impact report.

Following the successful elimination of rats and mustelids from Miramar Peninsula, the project has been entrusted to the local community for ongoing biosecurity management. Returning control to the community does not equate to abandonment; rather, it signifies a high-trust collaborative effort.

This community partnership is not only working, but is achieving results at a fraction of the cost.

The Miramar Peninsula biosecurity response depends on a vigilant community of 20,000 residents as our eyes and ears, reporting any sightings via our dedicated 0800 NO RATS number. Additionally, a skilled volunteer team, intimately familiar with the local environment, plays a crucial role in maintaining the area’s biosecurity.

This is supported by our existing detection camera and trap network that can be reactivated as needed and specialist detector dog teams who can respond to incursions almost immediately. Through our Predator Free 2050 networks and foundation partners we also have on-call experts available to offer support, tools and advice.

With this team in place, we can successfully manage incursions in our biosecurity zones, and protect our hard won gains in an efficient and cost-effective way. For the stoat incursion on the Miramar Peninsula, we were able to successfully manage the incursion in not only a similar timeframe to previous predator free island responses, but also at just 3% of the cost*.

How we caught the stoat

Identification

On 12 December 2023, volunteer Michelle Wilhelm identified a stoat on camera.

On 12 December 2023, volunteer Michelle Wilhelm identified a stoat on camera.

Over the following seven months, Predator Free Miramar volunteers checked images weekly, seeing the stoat nine times on camera.

Expert analysis determined we were chasing a lone male stoat which changed our risk profile; a pregnant female would need a different response!

Making decisions

With full support from the Miramar community and our team making great progress in Phase 2, we had some decisions to make. We are finely balanced between moving forward with the project and ensuring we are detecting and removing invaders from areas we have cleared.

Working with our technical partners (ZIP) we made the call to trust our detection cameras and our highly skilled Predator Free Miramar volunteers.

And it worked!

If you were a stoat, where would you go?

Stoats can travel over 70 km when they are finding their own territories. They can also easily swim 3 km between islands. So we were working with a big territory.

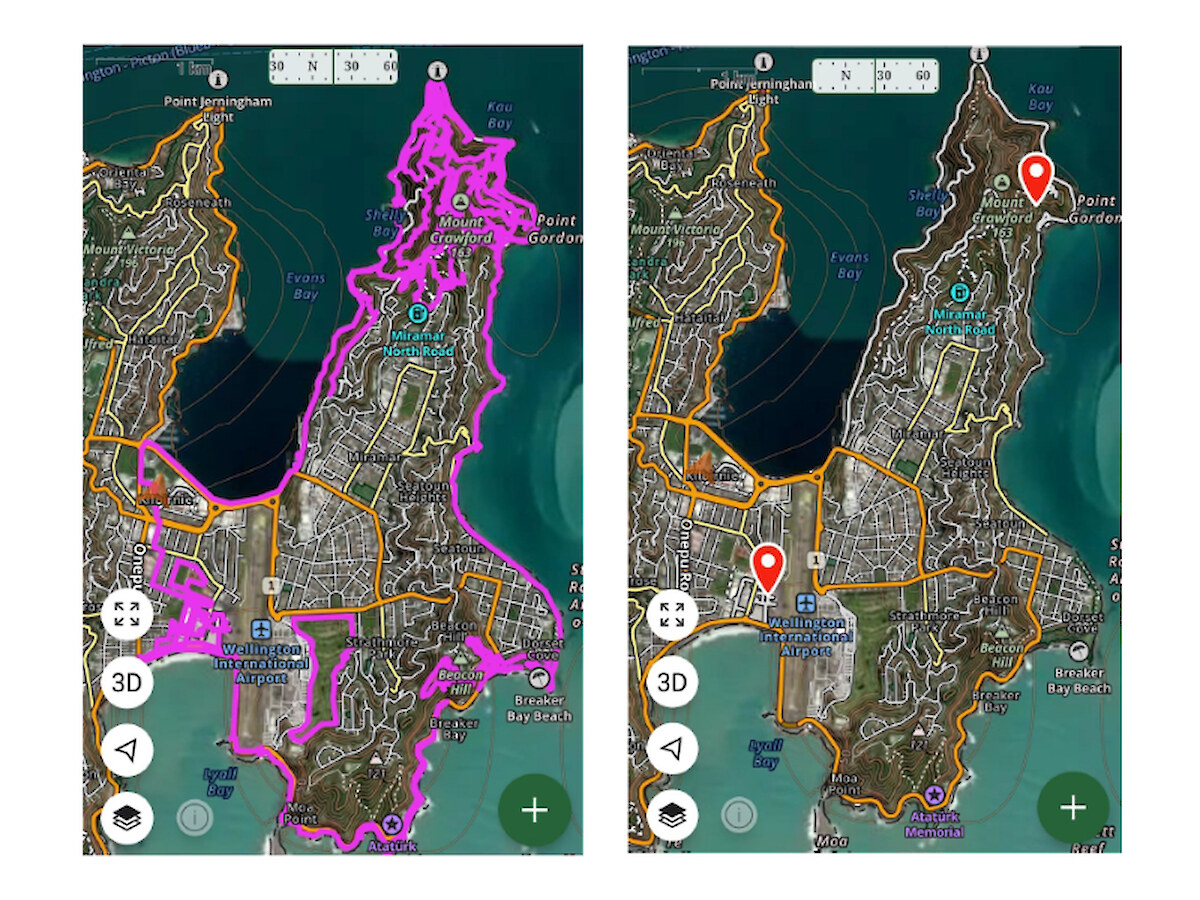

Our cameras showed this stoat appeared to have a base in the Northern Bush, but it was also spotted on camera at Oruaiti, Beacon Hill, Maupuia and Lyall Bay. It may have even travelled as far as the city.

We engaged Brad Windust and his stoat scat detector dog Wero to scout the peninsula. They searched for signs of mustelids, food caches, dens, play sites and scat. After scouting the peninsula for a week Wero indicated one site in northern Miramar as a play site and one potential place of interest in Lyall Bay.

Brad’s gut feeling was this stoat was only a visitor to Miramar, explaining he would have found more scat if it was living there.

Bringing in the experts

To support our response, we enlisted John Bissell from Backblocks Environmental Management to share his expertise. This empowered and equipped the Predator Free Miramar volunteer crew to lead the response.

John uses a mix of science, hunting and gut instinct. He specialises in targeting one animal in a large landscape.

John advised the crew: “The stoat is not just going to blindly walk into a trap just because it happens to be there… You have to think like a stoat.”

And that called for a change in strategy and mindset.

Leaning in to the hunt

Leaning in to the hunt

The skills of the Predator Free Miramar volunteers extend so far beyond basic trapping. They call themselves the ‘flying squad’ and are creative problem solvers who volunteer most Sundays.

Every weekend since the first stoat sighting in December, volunteers were rebaiting and moving traps near to where the stoat was seen. But there was an underlying sense of frustration after months without success.

Following John’s visit, the volunteer trappers had renewed confidence and a deeper awareness of what was needed to catch this stoat. They knew it was a fool’s errand to manage hundreds of traps; instead they needed to do a handful of traps really well. They chose premium sites that were freshly baited and beautifully presented.

Years of trapping rats meant they knew the landscape intimately. Features like ridges, streams and roads guided their thinking. Bush edges and fence lines hid the stoat from predators like kārearea (NZ falcons) and kahu (hawks): these were good places for traps.

The trappers used heaps of fresh red meat (beef, mutton and venison) and stoat bedding. The tennis ball-sized bedding was a visual lure, with the idea that if the stoat wasn’t hungry it might be curious about finding a mate or fighting off another stoat.

A successful catch

After 207 days and 755 hours of volunteer time, the Predator Free Miramar volunteers caught the stoat in trap number BT302 (north of Massey Memorial). It was lured with aged venison and male stoat bedding.

The trap was cleared by Gerard Hutching and Mike Arnerich, two of Predator Free Miramar’s regular weekend trappers. The trap itself had been moved several metres into a better position six weeks prior by Mike and John Herrick and the new site (and lure) proved to be a winner.

In the end, Dan Henry (Predator Free Miramar Lead) believes it was a series of small decisions that made the difference.

“It wasn’t a super stoat that’s too smart. It was catchable, with effort, persistence and creativity,” said Dan.

The volunteers were given the freedom to lead the response and that was part of the appeal, along with the mateship and a sense of community.

This won’t be last stoat we encounter but we are pleased to have this one dealt with, and it provided a perfect testing ground for our community biosecurity response. We got the result and are defining a new model for biosecurity response at a fraction of the cost.

What we now know

The invading stoat was sent for genetic testing at Manaaki Whenua, revealing that the animal was a young male, born in September 2023. Likely dispersing in search of territory.

Genetic sequencing indicates that this stoat is most closely related to one previously caught near Makara Beach, followed by another from Tongue Point. These relatives are not from the same litter or parents, meaning they are more distantly related, like cousins or grandparents.

These findings highlight a significant geographic spread, as stoats are known for their ability to traverse considerable distances. Importantly, now that we know the likely origin, we can confirm that the stoat did not swim across the harbour to reach the peninsula; rather, it entered by land. Understanding these details helps us adapt and improve our biosecurity response systems.

*Cost savings were compared to a recent effort to remove a stoat from Chalky Island in Fiordland, which cost almost $500,000 NZD.

Posted: 9 December 2024